For almost 35 years, Spike Lee has chronicled black lives in his films from love, friendships, and family to racism and police brutality. The Oscar-winning director, 63, is well aware that real life doesn’t always have a happy ending and neither should his art. “No, that’s some other guy’s movies,” he says. As protests continue in America over the tragic deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd the last two at the hands of the police.

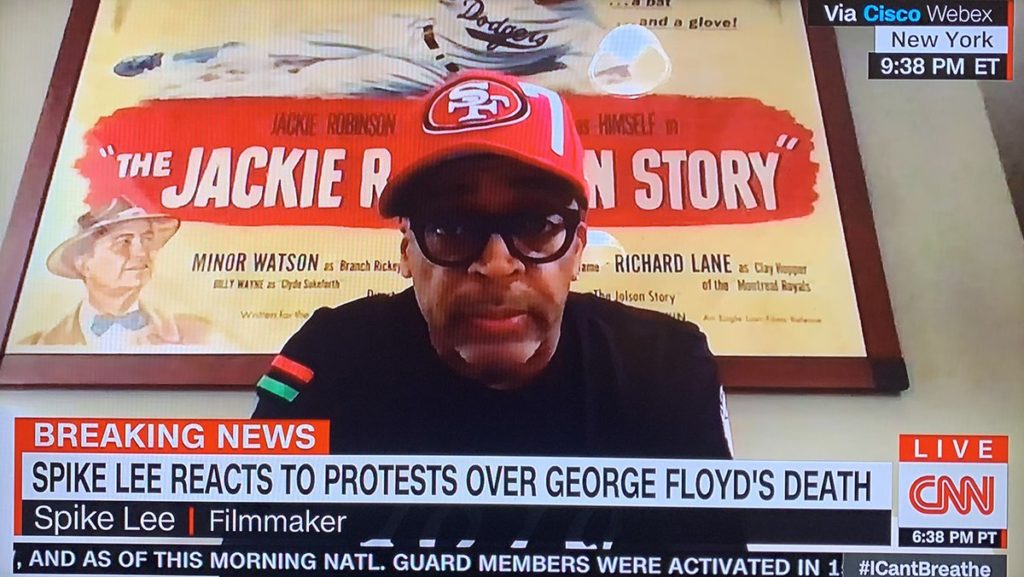

Lee’s films are now more poignant than ever. “They should be required viewing,” says actor Jonathan Majors, who stars in his new Netflix movie Da 5 Bloods. Lee’s 1989 film Do the Right Thing tells the story of a young black man in Brooklyn who is choked to death by a cop using excessive force. Anger, grief, and protests ensue. “What we’re seeing today is not new,” Lee told CNN on May 31. “We’ve seen this again and again and again.”

The next day he released the new short film 3 Brothers – Radio Raheem, Eric Garner, and George Floyd, which linked footage of the death of his fictional Do the Right Thing character with the two real-life men killed by police. “Why are people rioting? Why are people doing this?” Lee asked. “Because people are fed up, and people are tired of the debasing, the killing of black bodies … People are reacting the way they feel they have to be heard.” Lee understands their pain. He’sbeen showing audiences the injustices facing African Americans – and celebrating black culture on screen ever since his 1986 debut, She’s Gotta Have It, an influential independent comedy about a single woman dating three men in Brooklyn. More serious movies like Malcolm X followed as well as semi-autobiographical films like Crooklyn and School Daze and comedy-dramas like Jungle Fever and Mo’ Better Blues. Lee’s latest film, Da 5 Bloods, tackles a different type of black experience: serving in the military. Set in Vietnam, it’s an action-packed tale about veterans who reunite to reminisce and unearth some long-buried secrets. The film touches on the plight of black soldiers who fought and died for their country while facing racism and hatred back home. Their PTSD also usually went untreated. “After Vietnam, they were called baby killers, all kinds of stuff,” Lee says, adding that as a teen he watched the Vietnam War play out on the TV each night. “I think it’s a disgrace that with Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, you have soldiers who fought for this country who are homeless. That’s a travesty.